African American Women in Montana

The African American woman’s experience in Montana represents a small scaled snapshot of the larger national experience. African American women in Montana fought against the negative stereotypes that plagued both themselves as African American women, and those of their husbands and children. They used the concept of racial uplift to help build their communities, and then used their communities to transform the social realities of Reconstruction-Era Montana. The traditional social roles of American women placed African American women in a unique position to preserve and even create a community and its values. Their roles as mothers, homemakers, and housewives helped these women play a vital part in the development of African American communities in frontier towns of Montana through facilitating as well as participating in activities that traditionally bind members of a community. [1] Many community-focused organizations and activities were influenced by both major ideologies of the early 1900s, specifically Booker T. Washington’s advocacy for social and political accommodation versus W. E. B. DuBois’s active political protest, and the organizations and activities formed in response to local issues. [2] Tactics within each of these philosophies included creating benevolent societies and social clubs, and promoting an image of the African American family that differed from the negative stereotypical images of the turn of the century through church activities and displaying strong family values.

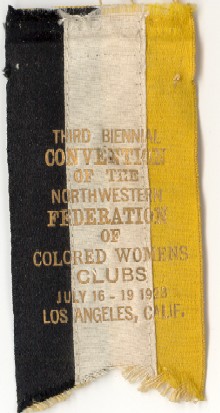

When discussing the African American social clubs, Quintard Taylor suggests that the men tended to view the women’s clubs as “women’s work or within the women’s sphere” and that they “grossly underestimated the role of these societies in simultaneously preserving traditions and values while improving black life in the city.” [3] These benevolent women’s clubs succeeded more in promoting the respectability of the African American people in the eyes of the larger society than many of the men’s clubs. The women’s clubs attempt to improve the general city life for their African American community often involved political engagement. Within the correspondences of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Club records, many women found themselves writing to their congressmen, senator, local businessmen, or even showing up in their offices to call attention to social injustices within their cities. Many of the clubs worked to raise money for the creation of day nurseries, scholarship funds for local girls and boys, and even getting the local libraries to carry books by important African American authors. [4] Many of the clubs worked to established daycares and kindergartens for working mothers, which happened on the national level when women in general entered the workforce during World Wars I and II.

All of these activities were attempts to reconfigure the stereotypical and negative views in which the larger American society viewed their African American community. Many of the same club women maintained themselves as churchwomen, knowing that such an influence would raise the moral standards of their families and increase their respectability within the larger community, and some African American women followed in the footsteps of Madam C.J. Walker in St. Louis by opening beauty parlors in Montana, in an attempt to build economic self-sufficiency and create a social community outside of the home or church where women could exchange ideas. [5] The Colored Citizen, a Helena African American newspaper in 1894, promoted several local shops and actually encouraged young women to go into business for themselves. [6]

As with most Montanans in general, the drought of 1917 and the lack of employment in Montana during the Great Depression and World War I forced a large number of African American families to leave for opportunities found further west. Even with their numbers dwindled; the women of the Montana State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs continued to work toward their goal of uplifting their community. In the 1950s and ‘60s, the group worked together to push anti-discrimination bills through the Montana legislature. Through a series of letters, phone calls, and telegrams, the women were able to increase support for a bill that many of the opposition viewed as unnecessary in Montana or feared the loss of business by allowing service to minorities. Scholarships continued to be distributed by the Federation into the 1970s. However, in 1963, the Federation could see that their population was becoming even smaller with very little chance of re-growth, and they voted in the conference the same year that, should the Federation find itself disbanding, the funds remaining in the treasury would be donated to a Montana University. The final conference held by the Federation was in 1971, the 50th Anniversary, and two of the remaining four associated clubs had disbanded due to lack of membership. In 1972, just one month before the 51st anniversary of the Montana State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs founding, the group disbanded and the remaining funds were donated to the University of Montana in Missoula to be used as a scholarship to any deserving student. [7]

Despite their relatively small numbers, African American women in Montana succeeded in building a sense of community in their cities through civic and political involvement. They inspired and even helped fund young African Americans in their college careers. They owned their own businesses, raised their children, and made sure Montana stayed up-to-date with the national Civil Rights movement. A small scale snapshot of the legacy of the African American Women’s history within the U.S.

Full Text With Citations (PDF)

When the Montana Federation of Negro Women's Clubs first met in Butte on August 3, 1921, at least nine African American women's clubs were active in communities throughout the state. In 1902, Butte residents founded the short-lived Afro-American Women’s Club. Women living in Kalispell formed the Mutual Improvement Club in 1913. Three years later, twelve Helena women met as the Pleasant Hour Club. The Pearl Club formed in Butte in 1918, and two groups, the Phyllis Wheatley Club in Billings and the Dunbar Art and Study Club in Great Falls, organized in 1920. Four local clubs formed in 1921: Bozeman Sweet Pea Study Club, Helena’s Mary B. Talbert Art Club, Clover Leaf Club in Butte, and the Anaconda Good Word Literary Club.

In addition to offering social activities for black women, the local clubs and the state federation supported scholarships, lobbied for civil rights legislation, and worked to improve racial relations at the state and local level. At its annual meeting in 1948 the Montana Federation voted to change its name to the Montana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs. By the 1970s only four clubs remained active, and on June 17, 1972, the state federation's executive board voted to disband.

According to historian Peggy Riley: “The National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs motto, ‘lifting as we climb’ reflects the commitment of black club women to improve the welfare of all black people, regardless of class, region, religion, or educational level.” (Riley in African American Women Confront the West , 1600- 2000, p. 127.)

The Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs Records are housed at the Montana Historical Society, and the finding aid, including more historic context, is available through the Northwest Digital Archives. For more information about the clubs, visit “Lifting as We Climb: The Activism of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs” on the Montana Women’s History website.

Sarah Bickford

Sarah Bickford’s compelling story takes place during the most contentious and formative decades of America’s – and Montana’s - history. Born Christmas Day, 1852 Sarah began her life as the property of John Blair in Jonesboro, Tennessee. Slavery in Tennessee ended in 1865, and Sarah moved in with her aunt, Nancy Gammon, in Knoxville. Sarah changed her last name from Blair to Gammon.

Sarah came to work for attorney John Lutrell Murphy and his wife Viola, caring for their two young wards. Murphy brought Sarah and the children to Virginia City, Montana Territory in 1870. Murphy and the children left soon thereafter, but Sarah stayed. She married John Brown, an African-American miner, and with him had three children. Sarah survived the death of her two sons, and later divorced Brown in 1880. Tragedy struck again when her daughter Eva passed away in 1881.

In 1883, Sarah married Stephen Bickford, a white farmer from the area. Together Sarah and Stephen had four children: Elmer, Harriet, Helena, and Mabel. Five years into their marriage, Stephen purchased a 2/3 interest in the Virginia City Water Company. Sarah inherited Stephen’s interest in the company upon his death in 1900, and purchased the remaining third from Henry Gohn, becoming the first African American woman in Montana – and perhaps the nation – to own and run a utility. Though Virginia City’s prospects declined over the subsequent decades, Sarah Bickford stayed on, becoming an intrinsic part of that tightly-knit community.

She died in her home in 1931, leaving an impressive legacy. Sarah’s story is indicative of the capability and tenacity required of those who not only survived great hardships, but helped create Montana’s diverse and enduring heritage.

Over the past several years, researchers, particularly Laura Arrata and her advisors Bill Peterson and Orlan Svengin, have shed new light on this fascinating woman’s experience. For more information check out their webpage Finding Sarah Gammon Bickford.

See also “Celebrating Sarah Gammon Bickford” on the Montana Women’s History website.

Emma Riley Smith

Emma Riley Smith spent her childhood in Arkansas, daughter of a farmer who longed to return to Africa. When Emma as 14, the family did just that, moving to Monrovia, Liberia. Sadly, her parents and her brother died within 15 years. Emma returned to Arkansas with her teenage sister, Thelma. Finding the situation of blacks in the rural south uncomfortable, Emma resolved to move on: “I had seen other places, and I didn’t exactly like the way the Negro was treated…I says ‘I couldn’t live here and take care of my sister and send her to school…There’s better places in America to live, and I’m going to find them.”(Riley in African American Women Confront the West, 1600-2000, p. 132)

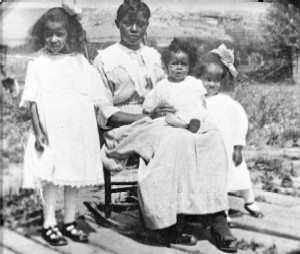

Emma arrived in Montana in 1913, and met and married Martin Smith in Butte. Mr. and Mrs. Smith moved to Lewistown, where he was a cook for the Milwaukee Railroad. Martin then went to work for the Great Northern in Great Falls. There they continued to raise their family: daughters Madeline, Alma, and Lucille and sons Martin and Morris.

In Great Falls, the family was quickly embraced by the AME church community. By 1927, Emma served as conference secretary for the church’s board of trustees, and continued in the position for nearly 30 years. In that capacity, she organized fundraisers, social, contests, and rallies. In addition to her church duties, she served with the Missionary Mite Society from 1937 to 1967, an organization that supported missionary work in Africa as well as the West. The City of Great Falls recognized her contributions to the community in 1967, naming her “Mother of the Year.”

For more information about Emma Riley Smith, see Peggy Riley’s article, “Women of the Great Falls African Methodist Episcopal Church,” in African American Women Confront the West, 1600-2000 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008).

Alma Smith Jacobs

Emma Riley Smith’s children were very accomplished, including her second-oldest daughter, Alma Victoria Smith Jacobs. Born in Lewistown in 1916, Alma moved with her family to Great Falls in 1924. An excellent student, she graduated from Great Falls High School, and attended college at Talladega, receiving her degree in sociology. While there, she worked in the college library, and upon graduation stayed on as an assistant librarian. Offered a scholarship to study at Columbia, she received her masters in library science in 1942. Alma returned to Great Falls in 1946, working at the city library first as a catalog librarian and later as the director. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, she worked tirelessly to expand the library services, as well as the library building, culminating in the new Great Falls Library constructed in 1967.

Her efforts with the library, in addition to her service to local civic groups, including the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and the Great Falls Interracial Council, earned her the title “Great Falls Woman of the Year” in 1957.

She moved to Helena in 1973 to serve as the State Librarian, a post she held until her retirement in 1981. Throughout the 1970s, she was president of the Montana Library Association, president of the Pacific Northwest Library Association, and was the first African American on the Executive Board of the American Library Association. She was active on the Montana Advisory Committee to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission and co-founded Humanities Montana. Together with her sister, Montana State University librarian Lucille Smith Thompson, she worked to publish The Negro in Montana: 1800-1945, a compilation of Montana black history resources.

On December 15, 1997, Alma Smith Jacobs died at the age of 81 in Bozeman. In 2009, the Great Falls Public Library dedicated a new outdoor plaza in her honor. The community also established the Alma Smith Jacobs Foundation to address social and economic issues.

For more information about Alma Smith Jacobs, see Ken Robison’s article “Alma Smith Jacobs: Exceptional Librarian, Community Leader, and Member of Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.” See also “Alma Smith Jacobs: Beloved Librarian, Tireless Activist” on the Montana Women’s History website.

Octavia Bridgwater

![Detail of Octavia Bridgwater in Montana State Federation of Negro Women's Clubs], Great Falls, Montana, July 15-18, 1951, MHS Research Center Photo Archives, #96-25.10](/Shpo/AfricanAmericans/AfAm_images/OctaviaBridgwater.jpg)

Octavia Bridgwater was part of a well-regarded Helena family. Her parents, Samuel and Mamie Bridgwater, were from Tennessee originally, and moved West, following Samuel’s military career. In Arizona they had their eldest daughters, Emma and Sophia. They moved to Helena in the 1890s. There they raised their large family of three girls and two boys. Octavia attended Helena High School. She then attended the Lincoln School of Nursing and State University in New York, graduating in 1930 with her registered nurse degree. Upon her return to Helena, she worked as a private nurse for a year, then began her long career with St. Peter’s Hospital. She worked there continuously until World War II, when she served as an Army nurse.

She joined the Army in 1943 and served during World War II. At this time, the Navy did not accept any black nurses and the Army had a quota of only 160. There were at the time 8,000 black nurses in the U.S. These women realized that if the military situation was not rectified, black nurses could never be integrated into the mainstream medical community. Nationally through the black press, the women mobilized for their cause. The Army and Navy lifted the boycott against black nurses in 1945. Octavia earned the rank of second lieutenant, and returned to Helena to work for St. Peters Hospital for many years. She was always proud that she was part of the national movement.

When she returned, she took in her niece and nephew, Margie and Eugene, who lived with her in her home at 502 Peosta. Former Montana Historical Society staff member Marlene Carbis lived down the street, and was good friends with Margie. Carbis remembers that the Bridgewater house was wonderful, and always neat as a pin. The community rallied around the family when young Eugene drowned at the quarry lake at Helena Sand and Gravel.

Despite the tragedy, Octavia continued to be a valued member of the community, not only at St. Peter’s, but as a member of the Missionary Alliance Church and the American Legion. And, of course, she attended numerous annual meetings of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. Ms. Bridgewater died in 1985 at the age of 82, and is buried at Forestvale Cemetery. In 1992, the Women in Military Service for America recognized Ms. Bridgewater for her service to the country and community.

For more information about Octavia, see Ellen Baumler’s article, “Helena Remembers Octavia Bridgewater,” Helena Independent Record, March 3, 2013. Her home at 502 Peosta in Helena is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Learn more about the house and the Bridgwater family in its nomination form.