African American Churches of Montana

By Anthony Wood

There is perhaps no fuller representation or more significant example of the legacy of Montana’s African American community than can be found in the stones, bricks, and stain-glass of its historic black Churches. In all, six African Methodist Episcopal congregations, and about a half dozen or so black Baptist churches, established permanent locations of worship in Montana between 1889 and 1950. In all likelihood, many other church bodies existed in the smaller cities and towns across the state wherever African Americans made their homes, but were without a physical building.

The early black community in Montana is characterized by four general periods of development: migration, opportunity, establishment, and finally exodus.[1] Following the Civil War, African Americans were eager and ready to move west with large contingents of other white Americans. While the homesteading boom ranked among the main drivers of white urbanites into the vastness of the American West, the tens of thousands of black men and women usually arrived through other means. Thousands of young (and some not so young) black men joined the 9th and 10th Calvary, or the 24th and 25th Infantry, and were sent out into the southwest desert to aid the westward movement of Americans to California.[2] By 1890, the shift of the black “Buffalo Soldiers” north to the Dakotas and Montana became the major precipitator of growth in the African American communities of Montana. Especially in western towns like Helena and Missoula, newly retired black soldiers found established communities where opportunity for social and civic participation was ripe, and where their wives and families could become integral members of a society with other black women and children. It was a far cry from the dusty tent cities that surrounded the Military outposts of the Southwest. Like the military, the Railroad also provided solid and steady work for black men seeking their future out west. Cities like Great Falls, Billings, Havre, and Miles City quickly sprouted small enclaves of African Americans and their families as the Northern Pacific Line struck its way across the continent.[3]

Many of the jobs that were available to African Americans lacked stability, and were seldom permanent. For this reason, the phase of opportunity in Montana’s black communities is characterized by searching for jobs and growing population centers so that local black businesses and other social endeavors could exist. Where this succeeded, the black community established itself as a viable social and ethnic group, with its own goals, agendas, and aspirations. In Montana, only Anaconda, Butte, Bozeman, Billings, Great Falls, Helena, Missoula, and Havre (to a lesser extent) succeeded in establishing and maintaining such communities for any prolonged period of time.[4] These eight major ethnic centers are characterized by the establishment of local black businesses, in some cases neighborhoods, fraternal organizations, women’s clubs, civic groups, and places of worship with other black men and women. In every one of the aforementioned categories, the local church was not only a factor of their success, but vital to their very existence.[5]

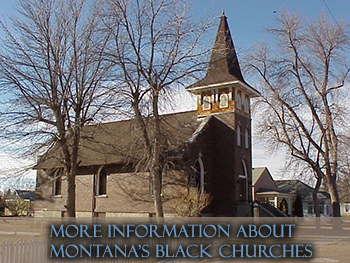

The existence of a physical church building and its relationship to the members of the community is vital to the establishment and growth of a neighborhood. Great Falls and Helena, each boasting sizable populations, saw the growth of such neighborhoods in close proximity to Union Bethel AME church in Great Falls, and St. James AME in Helena. In Billings, the African American residents were restricted, by social constructs rather than ordinance, to owning property on the city’s south side. When the congregation of Billings’ AME church purchased a building several blocks north of the railroad tracks, the neighborhood’s northern boundary, community members literally picked the building up, and moved the structure in tact eleven blocks south, to 402 South 25th Street, the heart of the black neighborhood.[6] Wayman AME Chapel still stands at that location today.

Perhaps the single most important aspect of community development that sprang from the sanctuaries of black churches, not only in Montana, but across the nation, was the fostering of vibrant, political aspirations. No separation of religion and politics existed on Sunday mornings. The theology of African American Christianity, founded in the struggle for freedom and equality reaching back to the Colonial America, continued to find biblical admonishment of repression, racism, and all manner of social and ethnic prejudice.[7] Often, the first cry for justice in matters, great or small came from the pulpit. For this reason, southern states prior to the Civil War made it a crime for congregations of certain denominations, such as the African Methodist Episcopal church, to hold services.[8] During Reconstruction (and sadly more recently) many of the most heinous and infamous acts of hate were directed at AME churches and their members.

In Montana and the West, the political aspirations that flowed from the church, manifested in the creation of a plethora of black Masonic Lodges and other fraternal organizations, women’s clubs, benevolent societies, and activist groups. In these pockets of self-segregated civic life, African Americans harbored and nurtured leadership and self- expression, in the face of institutional racism. The Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. whose motto was “Lifting as we climb,” worked to promote education, the family, and the status of black women in the home and the community. This state-wide organization had a significant impact on the lives of African Americans in Montana, as they fought to quell prejudice in the community, pushed for civil rights legislation in the Capitol, and helped dozens of black students pay for college. Like most of the many black groups, the MFCWC’s membership, and its physical location were in close proximity to the AME and Baptist churches of Montana’s cities and towns.[9]

The remaining black church buildings in Montana now stand mostly empty, or have new tenants. Union Bethel in Great Falls and Wayman Chapel in Billings are the only African Methodist Episcopal churches that still hold services in their historic location. Even so, their congregations are just a fraction of their past membership. The fate of the once vibrant black communities can be summarized by the fourth and final stage of Montana’s African American history, exodus. It happened suddenly. In 1910, the state appeared to be on the threshold of hosting a great western black society, by 1930, it was half its size, and by the end of the Second World War, it was all but gone. Why? The rains stopped falling from Montana’s big sky in 1917. The drought that ensued continued right through the winter of 1918 and into the hottest and driest summer on record. The homesteading boom crashed, flooding Montana’s cities and towns with thousands of desperate farmers and ranch hands in search of work. Jobs quickly became scarce as these new arrivals took work in professions that were historically available to the members of the African American community. The black men and women of Montana’s urban areas soon felt the hardships of unemployment. Meanwhile, the Great War in Europe had kickstarted a robust industrial economy on the nation’s east and west coasts. Seattle and Portland, in particular, attracted the Northwest’s unemployed workers with better paying factory jobs and thriving communities. When one adds to this the rise in racism engendered by an influx of rural white settlers, the exodus of many black residents is even more understandable.

Today, the ecclesiastical homes to once thriving congregations of African American men and women still stand in Anaconda, Butte, Billings, Great Falls, and Helena. They testify the legacy of Montana’s once thriving African American community.