Montana Women's History: Places

View Map

Check out these historic sites related to Montana women’s history!

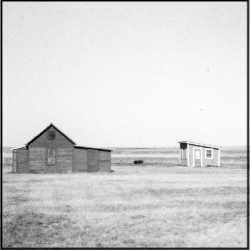

Anna Scherlie Homestead Shack, Blaine County

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 brought settlers to Montana and to this area called the Big Flat. Neil J. Scherlie was among the first to file a homestead claim and over the course of four years, three sisters and two brothers made claims nearby. Thirty-two-year-old Anna Scherlie arrived in 1913, becoming part of a long tradition of women homesteaders in Montana. In fact, in the four surrounding townships, women made up about one-fourth of the total homestead applicants. By 1916, Anna had forty acres planted in wheat, oats, and flax. Isolation on the Big Flat led many settlers to winter elsewhere and Anna followed suit. Legend has it that she went to St. Paul to work for the family of railroad magnate James J. Hill. Over the decades, Anna made few changes to her small woodframe shack, adding only a vestibule for use as a summer kitchen, a storage shed, and laundry. Droughts, depression, and two world wars passed. Anna remained here long after her neighbors had built modern homes, insisting that she was “too old for modern conveniences.” The Spartan lifestyle seems to have been Anna’s preference. When she died in 1973, an estate of more than $100,000 was divided among eighteen nieces and nephews; her ashes were scattered beneath a lilac bush on the property. Leon and Nellie Cederburg purchased the homestead when its seasoned resident moved to Havre in 1968. Rather than return the site to crop land, the Cederbergs maintain the homestead exactly as Anna left it. Return to Top

Bozeman Walking Tour

Connie Staudohar compiled this walking tour with Anne Banks, Linda Peavy, Ursula Smith, and Derek Strahn. Its introduction states: “Encompassing an area of Bozeman’s South Side that lies between the city’s Main Street business district, and the Montana State University (MSU) campus, this walking tour will acquaint you with many buildings that were central to the lives of some of Bozeman’s most notable women. You’ll also find streets named for the families from which these women came, a city park that was shaped by the benevolence of women’s organizations, and a school that symbolizes the early dedication of women to education even as it reminds us of the inequities women faced in employment… There are many other deserving women whose stories have yet to be told and this tour is only a beginning.” Download a PDF of the Bozeman Walking Tour by clicking here. Return to Top

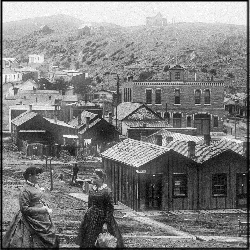

Butte Sites

St. James Hospital Nurses Dormitory, 300 West Mercury, Butte

The Sisters of Charity’s history in Montana began in 1869, when a group of six nuns arrived in Helena to establish their Rocky Mountain Mission. Within a year, they had started St. Vincent’s Academy, St. Aloysius Institute, and, responding to the great need for medical care in the mining community, St. John’s Hospital. Their resounding success led to other missions, including a call to Butte. In 1881, five Sisters of Charity arrived there from their motherhouse at Leavenworth, Kansas, to found St. James Hospital. Throughout much of their history, Catholic sisters did not focus on establishing or running hospitals, instead working with children as teachers. As the United States expanded, however, and settlers needed health care in the remote reaches of the country, several orders answered the call. In Butte, the sisters opened a school of nursing in 1906. Under Sister Superior Mary Marcella Reilly, the residential dormitory for students and nurses was built in 1917 to meet the latest standards required for school accreditation. For more than six decades, the St. James School of Nursing was renowned for its topnotch graduates. Original exterior details, including the handsome leaded glass and copper awning with its cross above the entry, are reminders of the contributions made by the benevolent Catholic sisters to medicine and education in Butte.

Butte Red Light District Walking Tour

Most of the cribs and “parlor houses” that once lined Mercury and Galena streets are gone, but this walking tour will help you imagine life in Butte’s tenderloin, where at one point as many as a thousand women of all ages, races, and backgrounds vied to make a living. Download a PDF of the Red Light District Walking Tour by clicking here.

More Butte Sites on History Pin

Richard Gibson of the Digital Copperway Project has created a women’s history tour, with text and historic photographs on an interactive map of Butte that reflects how women experienced, and contributed, to the city’s rich history. Return to Top

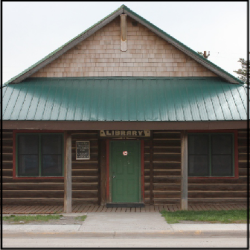

Carnegie Library, Red Lodge

The Red Lodge City Library opened in the Savoy Hotel in 1914 thanks to the efforts of the Women’s Club of Red Lodge. The hotel, however, was just a temporary home. The Club soon took up the campaign to secure a permanent library facility. The city appropriated $1,000 toward the effort and agreed to apply to the Carnegie Foundation for assistance. The Foundation awarded Red Lodge $15,000. In return, the city promised to provide land upon which to build and annual maintenance. Before the issue could be put to public vote, World War I intervened. At the close of the war, the city successfully applied again. Billings architect W. K. Kendrick drew the plans to conform to Carnegie standards, which included modest Classical detailing, meeting room space, open stacks and a central desk for the librarian. Construction began in 1919, and in March of 1920, the city library moved into its new quarters. The library, still in use today, is a tribute to the Carnegie Foundation and the determination of the Red Lodge Women’s Club. Return to Top

Caroline Lockhart Ranch

Born in Illinois in 1871, Caroline Lockhart spent her childhood on a Kansas ranch and went on to work as a writer and reporter in Philadelphia and Boston. Lockhart moved to Cody, Wyoming, in 1904, writing novels and screenplays, and working for the Denver Post. She bought the Cody newspaper, the Park County Enterprise, renaming it the Cody Enterprise in 1921, and sold it in 1925. The next year she bought an isolated ranch in Montana’s “Dry Head” country, and oasis in one of the most barren parts of the state. Starting with 160 acres, she added land through purchase, homesteading, and leases until she controlled over 6,034 acres. From the previous owners, Caroline inherited a two-room cabin, a few run-down sheds, and 20 acres of cultivated ground. Lockhart added onto and landscaped the area around the cabin with irises and hollyhocks, cottonwood trees for shade, and stone pathways. She constructed fences, corrals, and irrigation systems and added up to 15 structures, some reassembled from acquired property. One of her favorite spots was a rock table and bench constructed high on a bluff overlooking the ranch. The location served as a favorite spot to write. She published one novel, The Old West and the New, in 1933, while living at the ranch. Today, her ranch is open to the public as part of the Big Horn Canyon Recreation Area. Visitors who wish to drive, rather than hike, to the ranch buildings should contact 307-548-2251 to make arrangements. Return to Top

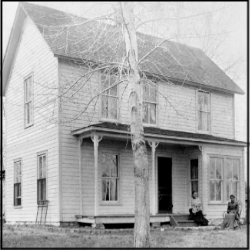

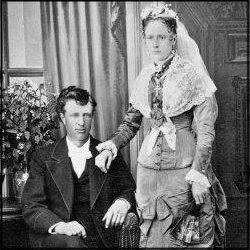

Charlie and Nancy Russell Honeymoon Cottage, 20 S. Russell Drive, Cascade

The son of a wealthy St. Louis family, Charles M. “Charlie” Russell longed for western adventure. In 1880, at fifteen, he convinced his parents to let him visit Montana. He never looked back. For over ten years, he worked as a night herder during the summer and rode the grub line in the winter, all the while painting and sculpting western scenes. Russell met Ben Roberts in 1882. The two became friends, and after Roberts married Lela Gorham and moved to Lela’s hometown of Cascade, the cowboy artist often visited him in the off season. While visiting Cascade in October 1895, Russell met sixteen-year-old Nancy Cooper, who lived with, and worked for, the Roberts. Nancy and Charlie married a year later in the Roberts’ parlor. After the ceremony they moved into the small bunkhouse and studio behind the Roberts’ house where Russell always stayed when he visited the family. Charlie’s marriage to Nancy marked a turning point in his career, and Nancy’s business acumen is often credited for his professional success. Her management started early, and within a year of their marriage the Russells had moved to Great Falls, where Nancy correctly felt there would be a larger market for Charlie’s work. Return to Top

Conrad Mansion, Kalispell

In 1853, young English immigrant Catherine Coggan fell for a charming, well-to-do widower named James T. Stanford. The couple married two years later, and eventually had three children. They lived comfortably in Nova Scotia until James died, leaving the young family in debt. Eldest son James Jr. joined the Canadian Mounties, stationed at Fort McLeod. A few years later, Catherine boarded the steamer “Dacotah,” with sixteen year old daughter Alicia (“Lettie”) and young son Harry, bound for Ft. Benton to be closer to James Jr. Soon, Lettie and a partner opened a school for children. As very few young, single women lived in Fort Benton, and few as beautiful as Lettie, young men often came calling, but local entrepreneur Charles Conrad won her heart. Charles and Lettie moved to Kalispell, where she the ran household, oversaw the servants, and cared for her mother and her mother-in-law who both lived with the family. Lettie actively served in the community. The Daily Interlake called her “one of the most public spirited and best known women in northwestern Montana.” She took an active part in public welfare issues, and her acts of charity and kindness were widespread. After Charles’ death in 1902, Lettie became the administrator of his estate. Lettie also took charge of the Conrad Buffalo Herd and eventually knew more about managing a wild herd in captivity than any person in the United States. During World War I, she served as Regional Director of the Red Cross and traveled extensively in this role. During the Spanish flu epidemic, Lettie directed nursing efforts and relentlessly recruited volunteers. Each Christmas, she held a party for all Kalispell’s needy children. Rev. H. S. Gatley eulogized: “Despite great responsibilities and a very busy life, she had retained a close contact with people in all walks of life, and had ever been ready to give of her time and substance where most needed.” Return to Top

Deer Lodge Women’s League Chapter House, 800 Missouri, Deer Lodge

Women’s suffrage was at the political forefront when Edward Gardner Lewis, a St. Louis promoter and publisher of women’s magazines, founded the American Women’s League in 1908. Lewis saw the League as the perfect means to promote American womanhood. Among several League institutions he founded was a correspondence school called the People’ University. Chapter houses across the country served as University branches. League membership was achieved through magazine subscription sales or pledges of $52 worth of Lewis’ publications. In exchange, the League constructed 39 local chapter houses in 16 states including two in Montana at Avon and Deer Lodge. Deer Lodge women’s groups banded together to collect the requisite subscriptions and C. D. Terret donated the lot. This Prairie style bungalow, designed by St. Louis architects, was built according to one of five standardized chapter house plans. Financial reversals sent Lewis into bankruptcy as this house reached completion. Founding League member Alma Bielenberg Higgins appealed to her father, Nicholas J. Bielenberg, who purchased the mortgage. He donated the building to the women of Deer Lodge in memory of his daughter, Augusta, who died in 1901. The Deer Lodge Woman’s Club has since maintained the facility, which has always served its intended function as a women’s cultural, literary, and social center. Return to Top

Ferris / Hermsmeyer / Fenton Ranch, Madison County

The lands of the lower Ruby Valley opened for settlement in 1863, shortly after the discovery of gold in nearby Bannack and Alder Gulch, but before any government survey of the land. A resident of several western mining communities during the 1850s, Jane Ferris arrived in the lower Ruby Valley in 1872, following the death of her husband. She took advantage of economic opportunities created by federal land law and the gold boom to secure land and a home for herself and her two small children under the 1841 Preemption Act. This law encouraged settlement in the American West by widows and heads of household on any 160 acres of unsurveyed land. Jane Ferris appears to be the only woman in Sheridan-area history to use preemption to secure land during Montana’s formative decades of the 1870s and 1880s. The 1866 cabin portion of the main residence and 1866 barn stand as a testament to Jane Ferris. See the National Register Nomination for more information. Return to Top

Glacier Park Women’s Club, East Glacier

Women in the nineteenth-century American West faced many challenges, not the least of which was maintaining cultural and social ties to their counterparts in the more “civilized” East. As women traveled west they left behind female family members, friends, churches, schools, and women’s organizations—all part of an intricate social support system. The popular image of women as “gentle tamers” in the West stems in part from women’s efforts to maintain or rebuild those support systems. Women’s clubs were often at the center of these efforts. By the early 1890s, the women’s club movement thrived in the United States. Over time, the clubs changed to meet the demands of growing communities and changing roles for women. By 1901, Montana boasted over fifteen women’s clubs, with at least one in every major town. As women’s clubs flourished across the state, they provided an outlet for women to exercise their organizational and leadership skills. Helene Dawson Edkins, a woman of Blackfeet ancestry and the adopted daughter of one of East Glacier’s founding families, together with twenty-two other women, founded the Glacier Park Women’s Club on December 4, 1920. The club received its federation status from the General Federation of Women’s Clubs the following year. Edkins was active during the East Glacier club’s first four decades, serving as club president for many years and as a member of the board for the General Federation of Women’s Clubs of Montana. Although in some areas, women’s clubs were stratified by race and class, the Glacier Park Women’s Club welcomed, and continues to welcome, all interested women. Return to Top

Helena Sites

Helena Walking Tour

Ellen Baumler uses forty-one sites to detail the stories of Helena women and the institutions they founded, including St. Peter’s Hospital, Intermountain Children’s Home, the YWCA, Carroll College’s nursing program, and the Florence Crittendon Home. Bootleggers and nuns, boardinghouse keepers and music teachers, prostitutes and doctors, attorneys and clubwomen, suffragists and second-wave feminists all make their appearance in these pages, as they did on Helena’s streets. You can download a PDF of this place-based guide by clicking here. Return to Top

Bridgewater House, 502 Peosta, Helena

During the early 1890s, diverse groups of people—of different religions, ethnicities, and economic status—strove to make Helena a prosperous and welcoming community. Hattie Haight purchased the house at 502 Peosta Avenue in 1891 and lived there until 1893. While in residence, her home hosted the Baptist Church’s Immanuel Mission, which catered to the multi-ethnic, working-class neighborhood. When her husband took ill and died in 1894, Haight retained the home for its rental income. She used the money to support herself and her two small children. She sold the house in 1896 and eventually moved to live near her husband’s family in New York State. When an active and admired African American family moved into the house in 1915, it became a socially significant place for Helena’s black community. Mamie Bridgewater was the widow of Samuel Bridgewater, a veteran of the Twenty-fourth Infantry, a segregated black unit of the Army. When her husband died in 1912, Mamie moved herself and her five children closer to town from the Fort Harrison area west of Helena and worked as a domestic. She continued this work throughout her life, always scraping enough together to care for her children and grandchildren. Mamie Bridgewater was deeply religious, a leader of the Second Baptist Church, and socially active throughout her life. In 1915, she moved into the home at 502 Peosta, now known as the Bridgewater House. After Mamie Bridgewater died in 1950, her daughter Octavia continued to make her home at 502 Peosta. Octavia had graduated from Helen High School in 1925, and then attended the Lincoln School of Nursing, in New York, one of only two nursing schools exclusively for African Americans. She returned to Helena in 1930 with her nursing degree, but Montana hospitals refused to hire African American nurses, so she worked as a private nurse. At the onset of World War II, the Army Nurse Corps begrudgingly began to accept African American nurses into their ranks. Following the family tradition of service, Octavia Bridgewater joined the Army in 1942. During her military career, she earned the rank of First Lieutenant and received her officer’s training at the Tuskegee base hospital in Alabama. Her role in promoting and advocating for change in the military regarding African American nurses brought her a sense of pride and proved to be a life altering experience. Lieutenant Bridgewater returned to Helena and 502 Peosta after her honorable discharge in 1945. As racial barriers diminished, St. Peters Hospital began to hire black personnel. She served as a much beloved registered nurse in the maternity department at St. Peter’s Hospital until her retirement in the 1960s. Return to Top

Hester Suydam Boarding House, 209 W River St. Fromberg

Hester Suydam’s friendly home on Fromberg’s River Street welcomed guests from all walks of life. As a widow, Suydam ran the house to provide income for herself and daughter, Mary. She came to live here in 1907, moving her boarding business from the faltering coal mining town of Gebo to the more prosperous Fromberg community. An attempt to transport her boarding house from Gebo proved disastrous, as a wind storm demolished the building enroute. Not to be deterred, Sudyam had this two-story building constructed as a boarding house, and in 1910 she, her 24-year-old daughter, and a young servant named Nellie kept the business afloat. That year they boasted six tenants: a teacher, sales clerk, carpenter, fireman, miner, and the proprietor of the local pool hall. The only multi-family home in the community, the Hester Sudyam Boarding House stands as a reminder of the optimistic growth of Fromberg through the first part of the twentieth century, and the determination of these women to succeed in the face of adversity. Return to Top

Holy Rosary Hospital, Miles City, Custer County

Religious orders were incredibly important to building Montana’s health care infrastructure. Originally a teaching order, the Presentation Sisters entered nursing after a 1900 diphtheria epidemic, establishing hospitals in Aberdeen, Mitchell, and Sioux Falls, South Dakota, as well as in Miles City. As did other Presentation hospitals, Holy Rosary offered a nursing certificate within a year of its opening. The 1918 influenza epidemic increased support for the hospital, allowing the sisters, who had purchased the building from the county in 1919, to expand their operation. Built in 1922, the flat-roofed annex boasted modern medical and surgical units and increased the number of available beds to eighty-five. The Presentation Sisters managed the hospital through drought, depression, and war, before constructing a new hospital in 1948. Learn more about Holy Rosary Hospital by reading its National Register Nomination. Return to Top

Lott Birthing Hospital, 128 South Yellowstone, Livingston

The very early Westside home at 128 South Yellowstone was the first on the block, built during the year Montana achieved statehood in 1889. During the late 1920s, the residence became the Lott Birthing Hospital run by local nurse Edith Lott. During the first half of the twentieth century, maternity patients were not usually kept in regular hospitals, but many families from the vicinity would come to town to give birth. Soon Lott’s services were in high demand, and she purchased the large house at 322 Callender to serve as the hospital and her home. Originally from Illinois, Lott’s large family moved on to Iowa. Though she only received an 8th grade education, she did train as a nurse, and went on to work as a single woman in that profession in Hall, South Dakota. By 1920, she farmed with her partner Minnie Miller in Silver, Montana between Marysville and Helena. In 1930, she lived at her hospital at 322 West Callender in Livingston with three employees: cook Julia Sanders, and nurses Madell Haukaas and Kathryn Paul. The hospital housed Ms. Lott, her daughter Betty, and various employees through 1947, when Nurse Lott retired.[1] Renowned for her compassion, she never asked if a patient could pay. By the 1950s, shifts in medical care practices led to the closure of maternity hospitals nation-wide in favor of maternity wings in modern hospitals. By 1954, she lived with Betty on South 2nd Street in Livingston, but returned to the hospital she loved, this time running it as the Pioneer Rest Home, through the 1950s. Return to Top

Missoula Sites

Gleim Building I & II

Brothels, politely marked on historic maps as “female boarding” houses, appeared on the west end of Front Street early in Missoula’s history. The red light district flourished there for three decades, particularly after the railroad’s arrival in 1883. One of the madams was Mary Gleim, whose large frame and aggressive nature made her notorious. Despite this reputation, she also reportedly had a sharp wit and a generous heart toward her family and those she liked. Born in Tipperary, Ireland, in 1846, she married St. Louis native John Edgar Gleim in England in 1870. The couple arrived in Missoula in 1888, and Mary quickly invested Gleim family money into property in the red light district, where she owned eight houses of prostitution by 1890. During the early 1890s, she commissioned the brick buildings at 255-57 and 265 West Front Street to replace earlier wood frame structures, a testament not only to her flourishing business, but also city laws that prohibited wood construction in the commercial area. A ruthless businesswoman, Gleim had numerous brushes with the law, but none more serious than in 1894, when she stood accused of conspiracy to commit murder. She allegedly hired two men to blow up the home of her rival Bobby Burns—with Mr. Burns inside. Convicted to fourteen years in prison, she served just over a year, freed after a retrial. Her happy homecoming proved brief, however, as her husband died of “chronic gastritis” in 1896. Over the next eighteen years, Mary Gleim continued to expand her business interests. She reportedly smuggled lace, diamonds, opium, and Chinese laborers. She invested in property throughout western Montana, and by the time of her death in 1914 was worth over $100,000. A city ordinance banned prostitution in 1916, after which the female boarders along West Front Street no longer openly practiced their trade. Return to Top

Mrs. Lydia McCaffery’s Furnished Rooms, 501 West Alder, Missoula

At the turn of the century, social critics saw apartment living as morally suspect. Instead, single working men and women who could not stay with their families typically lived in rooming or boardinghouses, where housekeepers ostensibly kept an eye on their behavior. Housekeepers were typically women, as the business was one of the few options for married or widowed women to earn a living. The need for rooming houses was great; Missoula’s population had grown over 250% between 1900 and 1910, and people continued to flock to the booming community. Lydia McCaffery and her widowed daughter, Mary Kroll, had this rooming house constructed in 1910 shortly after Lydia’s husband moved to Mexico. McCaffery expanded the two-story brick building circa 1915, adding dormers, which created space for three new rooms in the attic; a back addition with a kitchenette; and a separate wood-frame home in the rear, which she also leased to tenants. A diverse population rented Mrs. McCaffery’s furnished rooms. They included a dance teacher, a shoemaker, carpenters, railroad conductors, nurses at the neighboring hospital, and the widowed cook at the Northern Pacific Railroad’s lunchroom. Lydia died in 1921, and her daughter, by then remarried to local rancher George McCauley, took over the business. The McCauleys continued to live here and manage the rooming house into the late 1940s.

University of Montana – Women’s History Walking Tour

Women have a long and distinguished history at the University of Montana. The first two graduates were Ella Robb Glenny and Eloise Knowles. of the seven original faculty members, three were women. The 1893 University Charter promised: “the instruction of young men and women on equal terms.” By 1903, women had their own building on campus. This tour celebrates many of the buildings–here and gone–where women have made their impact at the University of Montana. Download the walking tour by clicking here.

Return to Top

Margaret McCarthy Homestead, Glacier National Park, MT

Margaret and Jeremiah McCarthy built the homestead house near the North Fork of the Flathead River in 1908. When her husband died that winter, Margaret decided to prove up the homestead claim. They raised a small garden as well as timothy and oats for their horses. She and her five children split their time between the homestead and Butte, where her children attended school and she ran a boarding house. Return to Top

Morgan-Case Homestead, Philipsburg vicinity

Annie Morgan was an African-American woman born into slavery in Maryland who, at age 44, reportedly came West as a cook for the 7th Calvary. Morgan left Custer’s service sometime before the Battle of the Little Bighorn and made her way to Philipsburg. Joseph “Fisher Jack” Case met Morgan in 1894. According to local history accounts, Morgan encountered Case by the banks of Rock Creek, where he lay stricken with typhoid fever. Morgan nursed Case, a Civil War veteran originally from New Jersey, and upon regaining his health he stayed on to fence her claim as payment for her services. In the course of Case’s convalescence the two apparently developed a mutual affection, and the couple lived together until Morgan’s death twenty years later. They supplemented Case’s war pension by selling strawberries and vegetables along Rock Creek and in Philipsburg, and by raising a few cows, goats and chickens. Fisher Jack and “Aunt Annie” took advantage of Rock Creek’s recreational appeal, earning extra income by providing campsites and a bunkhouse for hunters, fishermen, and other outdoor enthusiasts. Morgan filed a forest homestead claim on the property in 1913, but died just a year later. Morgan’s will was left unfinished and, despite her expressed wish that her home be left to her common-law husband, Joseph Case, ownership of the homestead remained in question. Case was advised by officials that although he had been living with Morgan ” . . . as man and wife . . . for over twenty years . . . he had no legal right to the place”. Case finally received a patent to the land in July of 1919, at the age of 74. Return to Top

Riverside (Daly Mansion), Eastside Highway, Hamilton, MT

Beautiful Riverside served as the summer residence of Margaret Daly, widow of copper magnate Marcus Daly, from its completion in 1910 until her death here in 1941. Daly himself had begun buying Bitterroot Valley land in 1887, eventually owning 28,000 acres. Their first summer house at Riverside was a large, rambling Queen Anne style home, but by the end of the 19th century, the Dalys began to plan for a major renovation in the Georgian Revival style. After Daly’s death in 1900 at a young age, Mrs. Daly oversaw the syndicate that ran her husband’s vast estate of business and properties. After six years, she began the four-year renovation of her beloved mansion, overseeing each detail. A talented and avid gardener, Mrs. Daly spent her summers at Riverside tending to the vast formal landscape. Mrs. Daly was well known not only as an astute businesswoman, but a generous benefactor and doting matriarch. Here benevolence included donating the land for the local library, constructing the Marcus Daly Memorial Hospital in Hamilton, supporting the Boy Scouts of America, and gifts to the Episcopal Churches in Hamilton and Anaconda. Family and friends joined her each summer, where she delighted in entertaining – from lavish meals to storytime with her grandchildren. When she died at Riverside in 1941, she had endured the deaths of her husband, daughter, and son. Her story is one of great wealth and generosity, but also strength and fortitude. Now a museum, Mrs. Daly’s gracious home at Riverside is a testament to the vision, talents, and generosity of one of Montana’s most influential women. Return to Top

Union Bethel, Great Falls

By the turn of the century, virtually all of Montana’s major population centers included thriving, though relatively small, African American enclaves. Constructed in 1917, Great Falls’ Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church stands as a testament to the African-American community in that city. Women played a crucial role in organizing and sustaining black communities in the West. African American women’s benevolent organizations developed both as an answer to exclusion from white women’s societies, and as a way to address issues unique to black women and their communities. Most often, they organized such groups from within an African American church. In keeping with the Progressive Era spirit, Union Bethel women formed organizations to benefit the church and community. Certainly one of the most active organizations to spring from the AME church was the Dunbar Art and Study Club, organized in 1920. A member group of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, the club performed charitable and literary deeds for the church and Great Falls for decades; it was especially active in promoting civil rights. Located at the Montana Historical Society, the Montana Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs’ papers are a rare and valuable historical resource. (“Papers of the Montana Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs,” Small Manuscript Collection #281, Montana Historical Society, Helena.) Return to Top

Virginia City, Walking Tour

Alder Gulch boomed with the discovery of gold in 1863. Nicknamed the Fourteen-Mile City, of the nine communities that sprang up along the gulch, Virginia City emerged as the largest. It quickly became Montana Territory’s first social, financial, and transportation hub. Throughout its history, much of what has been written about Virginia City has been written by men about men. The literature is heavily laced with the activities of the vigilantes and their controversial work. Much less has been written about the women. Although they were a minority in the male-dominated mining camp, women were integral to the community and a few played key roles. This tour of twenty-six sites shares some of the memorable women of Virginia City and the places that help tell their stories. Download the walking tour by clicking here. Return to Top

Where the Girl Saved Her Brother (Rosebud Battlefield), Big Horn County

By June 1876, the Great Sioux War had raged in southestern Montana for months. The Battle of Rosebud Creek on June 17, 1876 saw fighting between thousands of warriors and soldiers. The numbers, combined with the length of fighting, make Rosebud significant as the single largest battle of the Indian Wars. It also set the stage for Custer’s subsequent defeat at Little Bighorn eight days later due to the warriors forcing the withdrawal of General Crook’s column from the field. The Northern Cheyenne refer to the battle as “Where Girl Saved Her Brother,” and tell the story of Buffalo Calf Road Woman, or Brave Woman, who proved her valor in numerous skirmishes and battles of the war. At Rosebud, General Crook’s soldiers began their march along upper Rosebud Creek, but they were suddenly set upon by more than a thousand warriors who appeared seemingly from nowhere. The fighting raged for most of the day, a dramatic conflict that ranged across hills and ridges spanning five square miles. As the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne began to retreat, Buffalo Calf Road Woman’s brother, Chief Comes In Sight, lay wounded in the field. Seeing this, she turned her horse and bravely rode back, lifting her brother to her horse and saving his life. Tribal members and historians credit her valor as the turning point in the battle, when the Indian warriors rallied and continued the fight. In part because of the losses he sustained in the Battle of the Rosebud, Crook’s soldiers were unable to meet up with General George Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn a week later. Buffalo Calf Road Woman, however, participated with her husband at Little Big Horn, and witnessed the U.S. Army’s defeat. Indeed, Northern Cheyenne tribal historians credit her with delivering the blow that brought Custer off his horse and lead to his death. Of course, the United States went on to defeat the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne by the next year, changing the lifeways of the tribes forever. Buffalo Calf Road Woman, however, remains an inspirational figure in Northern Cheyenne culture. Return to Top

Wood Lawn Farm, Hobson

In 1881, Clarence Goodell and his bride, Parmelia “Millie” Priest, made the treacherous 300-mile journey from Helena to the Judith Basin. The Goodells built a log cabin there and staked a tree claim on the Judith River. By 1889, the enterprising Clarence was farming and ranching over 3,000 acres. That same year local builder Richmond Jellison began construction of the Goodells’ new wood frame residence in nearby Philbrook. There Clarence operated two local stagelines equipped with horses bred at the Goodell farm. Dubbed “Goodell’s Folly” by the locals, the Queen Anne/Colonial Revival home was a curiosity among the log cabins of the valley. Though its turret was removed after a windstorm and the porches are now enclosed, the residence appears much as it did when Millie applied her creative touches. Even today her peony bushes and hand-painted interior trim delight the eye. In the 1890s, Clarence served as state legislator and county commissioner while Millie was Philbrook’s postmistress. One of the area’s first women settlers, Millie often traveled miles to assist in childbirth or tend the sick, and the Goodell home was always open to those in need. The residence and still functional pre-1920s outbuildings symbolize the transition from frontier to farming community. Wood Lawn Farm today is the last thriving remnant of the once-vital settlement of Philbrook and a tribute to these resourceful pioneers. Return to Top