Edgar S. Paxson oil on canvas, 1912, 81" x 47"

(Photo by Don Beatty)

Paxson professed himself very moved by the story of the Salish-led spiritual pilgrimage from the Bitterroot Valley to St. Louis to find powerful white medicine—the Bible of the “blackrobes,” or Jesuits. Four groups of Salish Indians attempted the trip during the 1830s before Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J., answered their call in 1841. Presumably, this painting records the initial expedition of 1831. Against a background of the Bitterroot Mountains, the group’s determination is emphasized in the strong stride and concentrated expressions of the foreground figure.

Edgar S. Paxson, oil on canvas, 1912, 81" x 47"

(Photo by Don Beatty)

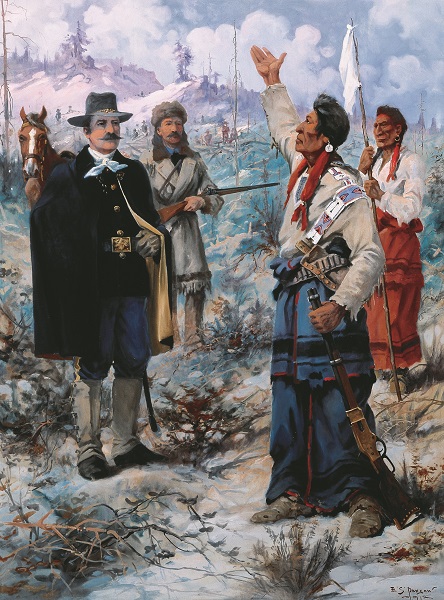

On October 5, 1877, Nez Perce leader Heinmot Tooyalakekt (1840–1904), popularly known as Chief Joseph, surrendered to the United States Army near the Bears Paw Mountains in northern Montana after a long, heroic struggle. Paxson captures the moment when Chief Joseph turned over his rifle and reportedly gave his famous speech, supposedly closing with the famous words, “From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” The artist tried to ensure accuracy in presentation, from the gesture of Chief Joseph’s upswept arm to the likenesses of the principal actors: Gen. Nelson A. Miles, Gen. Oliver O. Howard (in buckskin behind Miles), and Chief Joseph himself.

Edgar S. Paxson, oil on canvas, 1912, 81" x 153"

(Photo by Don Beatty)

The only one of Paxson’s six paintings that lacks a reference to historic personages, The Border Land comments on Indian-white interaction using generic types. Running along a diagonal that begins at the lower left, a creek creates a natural barrier that is also symbolic of a border between peoples. Settlers (he expressly avoids using trappers, explorers, or miners) encounter Indians who respond with an enigmatic gesture that may signify peace or, then again, halt.

Edgar S. Paxson, oil on canvas, 1912, 81" x 153"

(Photo by Don Beatty)

Two great moments converged for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in late July 1805: their arrival at the Three Forks that made up the headwaters of the Missouri River and Sacagawea’s recognition of her people’s hunting grounds from which she had been abducted five years earlier. The stream in the right mid-ground represents the importance of the geographical discovery. Sacagawea’s bold signal expresses the encouraging probability that her people would soon be found. Sacagawea’s pointing motion, although dramatically satisfying, was not a gesture that either the Hidatsa (her captors) or the Shoshone (her people) would have made. Clark (at left) and Lewis flank Sacagawea; to the right is her husband, interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau. At the far left are explorer John Colter and Clark’s African American slave, York.

Edgar S. Paxson, oil on canvas, 1912, 81" x 39"

(Photo by Don Beatty)

Meriwether Lewis’s arrival at the series of five waterfalls in Cascade County on June 13–14, 1805, evoked some of the most spirited reactions in all of his writings. Although he put his greatest praise on Great Falls and Rainbow Falls, he expressed tender regard for Black Eagle Falls because it boasted in its midst an island featuring a black eagle’s nest atop a cottonwood tree. Perhaps this is why Paxson chose to depict Black Eagle Falls in this painting, which includes the island with a cottonwood tree (but, surprisingly, no eagle’s nest). The standing figure on the left is Lewis; his companion in the picture cannot be identified because, in reality, Lewis undertook this particular exploration alone.

Edgar S. Paxson, oil on canvas, 1912, 81" x 39"

(Photo by Don Beatty)

Paxson depicts French-Canadian trader and explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varenne, Sieur de La Verendrye (1685–1749), who, in 1912, was believed to be the first white man to reach what is now Montana. More likely it was one of Verendrye’s sons who, in the company of an Indian war party on January 1, 1743, encountered mysterious “shining mountains,” possibly in the region of the Bighorn Mountains. Whatever the facts of the matter, Paxson distinguishes himself as the only the Capitol artists to depict the early French presence in the Northwest.