F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, each 84" x 48

(Photo by John Reddy)

This and the following statehood painting valorize government procedures, acknowledge the triumph of law over frontier conditions, and celebrate Montana’s coming of age after a long and painful struggle. The signing of the Enabling Act on February 22, 1889, “enabled” Montana to become a state once the requirements for a state constitution were satisfied. In the picture, Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard hands the bill to outgoing president Grover Cleveland as Joseph K. Toole, in his role of territorial delegate, looks on.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, each 84" x 48"

(Photo by John Reddy)

As the final step to statehood, President Benjamin Harrison signs the proclamation declaring Montana a state on November 8, 1889, in the presence of Secretary of State James G. Blaine.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 84" x 120"

(Photo by John Reddy)

On July 19, 1805, journeying up the Missouri River from the Great Falls to the headwaters at the Three Forks, Meriwether Lewis and his men passed through a spot where the river narrows alarmingly, slicing the land into high cliffs on either side. Lewis named it the Gates of the Mountains, a geographical designation still used today. The decision to depict a historic landscape rather than a peopled event (the only one among the Capitol’s seventeen paintings by F. Pedretti’s Sons) was Governor Toole’s.

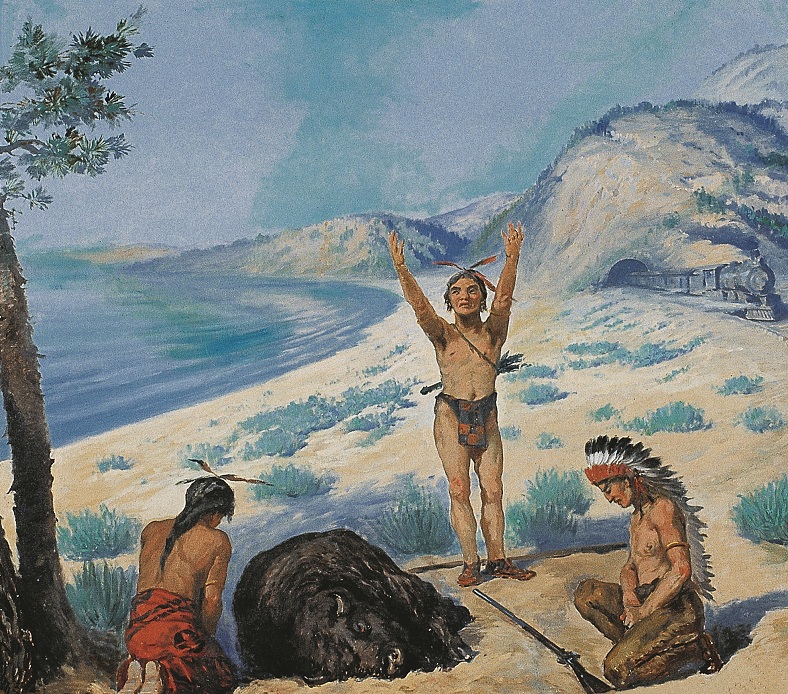

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 84" x 120"

(Photo by John Reddy)

In Farewell to the Buffalo, a companion to the above image, Indians pray over the corpse of the last buffalo as a train enters the picture space at the right. In spite of its benign appearance, the railroad was not the innocent agent of neutral progress, but a key factor in bringing about the very tragedy depicted in the painting.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 84" x 132"

(Photo by John Reddy)

So important did the Lewis and Clark Expedition seem to turn-of-the-century Montanans that all of the Capitol artists except Joullin painted the subject. In this piece, F. Pedretti’s Sons depict Meriwether Lewis viewing for the first time the formidable mountain ranges that lay between the Corps of Discovery and the Pacific Ocean. Using an unusual visual strategy, the Pedretti artist invites the viewer to experience the moment through the act of Lewis’s observation rather than focusing on what he actually saw.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 84" x 132"

(Photo by John Reddy)

Although native attacks on emigrants did occur in Montana, they do not constitute a major aspect of state history. Did white fear of such an occurrence make it seem a more defining event in their history than the actual number of incidents would suggest? In appropriating this element of the classic western saga for Montanans, perhaps Governor Toole also thought to honor families, as well as mountain men and prospectors, as part of the heroic era of Montana’s past.

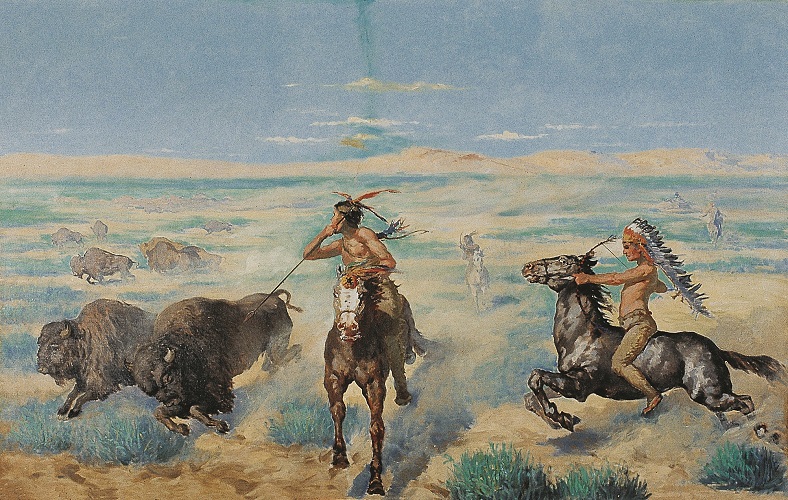

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 84" x 132"

(Photo by John Reddy)

The Chase of the Buffalo portrays the life and presumed death of Plains Indian culture as it was understood at the beginning of the twentieth century. The chase scene, long a favorite of western artists, signified the traditional buffalo economy of Montana natives.